- Home

- Parris Afton Bonds

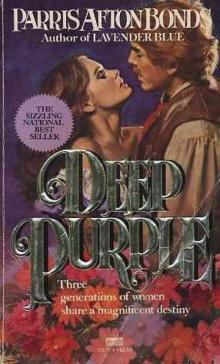

Deep Purple

Deep Purple Read online

PARRIS

AFTON

BONDS

DEEP * PURPLE

Published by Paradise Publishing

Copyright 2013 by Parris Afton, Inc.

All Rights Reserved

Cover artwork by Telltale Book Covers

This is a work of fiction and a product of the author’s imagination. No part of this novel may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away.

BONUS

First chapter of my novel THE MAIDENHEAD is at the end of DEEP PURPLE

The author is grateful for permission to reprint excerpts from the following:

“I Want You” by Arthur L. Gillom, found in The Family Book of Best-Loved Poems, edited by David L. George, published by Doubleday & Co, Inc., © 1952 by Doubleday & Co., Inc. Reprinted by permission of Doubleday & Co., Inc. and Copeland and Lamm, Inc.

“It’s Been A long, Long Time,” lyrics by Sammy Cahn, music by Jule Styne. © 1945 Morley Music Co. © renewed 1973 by Morley Music Co. International Copyright Secured. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.

“You Made Me Love You (I Didn’t Want To Do It),” lyric by Joe McCarthy, music by James V. Monaco. © 1913 Broadway Music Corp. © renewed 1941 by Edwin H. Morris & Company, a Division of MPL Communications, Inc., and Broadway Music Corp. International Copyright Secured. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.

.

Want You

I want you when the shades of eve are falling

And purpling shadows drift across the land;

When sleepy birds to loving mates are calling—

I want the soothing softness of your hand.

I want you when in dreams I still remember

The lingering of your kiss—for old times’ sake—

With all your gentle ways, so sweetly tender,

I want you in the morning when I wake.

I want you when my soul is thrilled with passion;

I want you when I’m weary and depressed;

I want you when in lazy, slumberous fashion

My senses need the heaven of your breast.

I want you, dear, through every changing season;

I want you with a tear or with a smile;

I want you more than any rhyme or reason—

I want you, want you, want you—all the while.

Arthur L. Gillom

As a child, a young girl with coltish legs and dusky skin, I spent many anxious hours prowling the low desert and the craggy foothills of southeastern Arizona's Huachuca Mountains— anxious hours not just because I was trespassing on the forbidden Cristo Rey land grant but also because I was searching among the rocks and cactus-stubbled dunes for the Ghost Lady, hoping and praying I could get a glimpse of her and at the same time scared to death that I really would.

The army’s electronic proving grounds and the state's futuristic superhighways now desecrate a wilderness that knew only the tracks of the jaguar and coyote, the lonely soughing of the wind, and the gentle whisper of a lover’s words. Much has changed since then, yet the tales of the Ghost Lady persist.

The old-timers tell different versions of the woman who rode sidesaddle, sometimes on a blaze-faced roan and at others on a rangy bay. But in every version the Ghost Lady, dressed in a black formal English riding habit with top hat, always appeared first near a Joshua tree.

It is at that point the similarity of the versions ends. Some say she haunted that area of Cristo Rey because she was a tormented wraith looking for the lover denied her in life. And others say she rode the area, its barren deserts and rock-clad mountains and lush, grassy valleys, because her soul was condemned to wander Cristo Rey until the fifty thousand acres—and the Stronghold—were at last returned to her heirs.

Of course, I preferred to believe the latter . . . perhaps because at that young age my childish mind could not conceive of a love so great that it would transcend time and space. I had yet to taste of love’s binding passion. But in all likelihood I chose to believe that version of the tale because even then I knew, like my Ghost Lady, my soul would know no peace until I possessed what rightfully belonged to me . . . Cristo Rey.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

PART I

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

CHAPTER 1

1863

"The tests are all in, Catherine,” Dr. McFarland said.

He studiously wiped a handkerchief over his spectacles’ thick milk-bottle lenses, and Catherine realized he was afraid to meet her gaze.

Why, she could not imagine. Surely, after watching death claim the hundreds of men given into his hands by the rapacious War Between the States, one more death could not be that difficult to acknowledge. But then, she reminded herself, the good doctor had been in love with her mother for years.

“Dear Dr. McFarland,” she replied as she worked the fingers of her kid gloves onto her hands, “please don't imagine for one moment that I am incapable of shouldering unpleasant news. I have worked at your side too many times during the last year when Death came for its victim.”

She laughed then, a laugh husky with rare, humorous insight, and the aging doctor was once again stricken by the transformation—a rather common face made uncommonly beautiful. “But then it was not one of my family Death was seeking those other times, was it? I assume it is pleurisy?”

Dr. McFarland jammed his spectacles back on his bulbous nose. “Interlobular pleurosis, to be exact.” His walrus mustache fluttered with the grunt of exasperation he expelled. “But it’s not just your mother I’m concerned about. You’re wearing yourself ragged taking care of her and working here at the hospital also.” She fixed him with steady eyes that were neither green nor gray. Crème de menthe, her sister called the color. “But that is neither here nor there,” she said crisply. She fastened the buttons of her kid gloves. The gloves, like her dress, were meticulously mended so that only the most observant eyes noticed. “There is no justice in life—isn’t that what I have often heard you mutter?”

The doctor had the good grace to flush, realizing Catherine was referring to the times he had resorted to alcohol to alleviate the pain in his soul which no physician could heal. She was right—what man was doing to himself in the bloody Civil War was horrendous. He occasionally half wished he could die along with the men on the makeshift cots that crowded the hospital’s wards. Sixty-six years was too old. He had seen too much.

He regarded the woman sitting so properly on the other side of the desk. He was fond of Catherine Howard. Perhaps because of her mother—though twenty-six-year-old Catherine did not seem to possess her mother’s exotic delicate beauty as did Catherine’s sister. But what Catherine did possess that her mother and sister did not was a strength of will and an unsuspected courage demonstrated in her care for men mangled beyond recognition.

“Well, Dr. McFarland?” she asked, her hands clasped lightly in her lap. “What do you propose? Don’t bother to gloss over whatever you have to tell me. By this time I am all too familiar with pleurisy’s—effects.”

The old man complied. “Then I don’t need to tell you about the chills and fever, nor the hacking cough.”

“No, all that I know. Tell me rather how much time my mother has left—approximately, of course.”

The doctor’s shoulders hunched with the weight of the prognosis he had to impart. “No one knows much about the disease. We do know that the patient needs plenty of rest and treatment—what little we can give with our limited medical knowledge.”

Catherine rose, drawing the string closed on her reticule as tightly as if she were drawing it on her emotions. “I will see that my mother gets the best care I can g

ive her. Good afternoon, Dr. McFarland.”

Despite the frigid March air that blasted through Baltimore’s snow-packed streets, Catherine was perspiring as she maneuvered about the attic’s dusty boxes where her father’s belongings were stored. Then she located the crate with the word Books penned across in her father’s precise handwriting.

Her father had been a schoolmaster, and it was he who had taught her the appreciation of books and knowledge—of languages and histories; as her mother, the daughter of a wealthy shipbuilder, had taught her the appreciation for the finer things of life. But it was her father, Catherine reflected wryly, who in a way was responsible for the decision she had made that afternoon— the decision to head toward the gold fields of the West, for her father had done the same in 1850, the year after gold was discovered in California.

He had abandoned the wife who loved him so little, who found a schoolmaster’s salary inadequate contrasted to her former way of life. Disinherited by her parents for eloping with the schoolmaster, the pampered woman was left by herself to care for the thirteen-year-old Catherine and the six-years-younger Margaret . . . or rather Catherine was left to care for her mother and younger sister.

The newest gold fields were in Colorado and Arizona now, and that was where Catherine meant to go. That afternoon, when she returned from Dr. McFarland’s office, she stood before the long pier mirror and looked at herself ... the face made pallid by too little sunlight and her body emaciated to a rail thinness by too much work. The mirror told her she had little hope of courtship from war-weary men. No, they would have their pick of buxom, voluptuously curved young women, who outnumbered the men and were anxious for the taste of romance and marriage that the Civil War had long denied them.

It took only a moment to locate the Encyclopedia Americana. She began to scan the facts about Arizona, which had been a part of the Territory of New Mexico until only two weeks prior, in February, when the U.S. Congress had established it as a separate territory.

She read about the Hohokam Indians who had come to Tucson’s teacup valley long before the Spanish and whose origins were lost in the course of time. And she read about Tucson itself with its watchtowered walls. As a sleepy Spanish pueblo, the Royal Presidio of San Agustin de Tucson, it was the same age as the American Republic.

When the last light of the afternoon faded from the small attic window, she put away the thick book with the certainty that Tucson was where she would go—where hordes of men had migrated a decade earlier, where women were few. Out there in that barren territory she could earn the money to see that her mother received proper care. Out there she still might find the husband and children for which her own heart cried out.

CHAPTER 2

Catherine snuggled her hands deeper in the fur muff as Arizona’s new chief justice, William Turner, swore in the territory’s new officers. It was the last of December, and the snowy chill of a northern Arizona winter enveloped the travelers assembled at the tiny settlement of Navajo Springs, just across the New Mexico boundary line.

“A carpetbag government if ever I saw one,” said the stocky old man, the new territorial general surveyor, who stood next to her. Hiram Ogilvee was referring to the fact that all the officials, but for himself, came from Eastern states, most of them lame-duck congressmen.

Catherine couldn’t have cared less. She only wanted to climb back into the great blue army ambulance and get warm again; however, she graciously accepted the tin cup of almost frozen champagne and drank to the health of the new Arizona Territory.

The governor, John Goodwin, at last closed the inauguration ceremony with a speech of his hopes for the new territory. Catherine then translated the speech into Spanish for the benefit of the New Mexican soldiers who acted as escorts. It had been part of her arrangement with Goodwin when he agreed to let her accompany the officials to Arizona. She could only think how strange it was that they stood in the wilderness to inaugurate the territorial government, with no citizens of Arizona to greet them.

At last, grimly wondering what had happened to Arizona’s famed sunny climate, she climbed back beneath the ambulance’s white canvas cover. More then once in the three-month journey she had experienced second thoughts about her decision to come west. But it was too late to change her mind, she told herself firmly. The fact was she had signed with the Albert Teachers Agency listing service and as a result was now being bounced most uncomfortably in the ambulance as it lumbered southwestward toward the temporary capital. Fort Whipple.

Her sister and mother had been aghast that she could actually consider accepting a teacher’s position in what Margaret called a “godforsaken place on the frontier.”

The afternoon Catherine announced she had taken a position as a private teacher near Tucson in the Arizona Territory, her bedridden mother had caught her by the hand. “Catherine, you can’t do this. I’ll arrange to go to Europe. They’ve excellent spas there and good doctors. For God’s sake, I’ll get another opinion before I’ll let you go off to some dirty border town. Make her listen, Margaret!”

Margaret, beautifully dainty Margaret, had looked hopelessly from her mother to her sister. She picked up the letter from Don Francisco Godwin that lay on the pedestal table and glanced through it. “It’s quite outrageous, Catherine! No well-brought-up woman in her right mind would do such a thing. Papa always did call you his headstrong one.”

Catherine poured out a teaspoon of the elixir Dr. McFarland had prescribed for her mother’s “nerves.” The still-beautiful woman lay pale and gasping with the shock of the news—not the news that her body harbored pleurisy. This malady she had suspected for some time. What she could not come to terms with was losing the almost maternal support of her older daughter.

“If you would both stop to think,” Catherine said firmly, “you would realize that for one thing we have no money to go to those ‘excellent spas in Europe’ and that, working for the Godwin family, I will earn an enormous salary—more than I do working at the hospital.”

She turned away, mortified by her false gesture of nobility, and set the medicine bottle on the table. How could she admit to the base, petty jealousy that darkly colored her love for her sister—dear Margaret who had been the most sought-after young woman in Baltimore before the Civil War whisked away the men?

Catherine could remember watching from her mother’s upstairs dormer window as the young men came to call on Margaret. And she could remember sitting on the sidelines the few times she escaped her mother's bedside while Margaret danced one cotillion after another.

Oh, Catherine was very much aware of Dr. McFarland’s high esteem for her brave decision to go west in order to earn a living to support her mother and sister. But what Dr. McFarland and her mother and Margaret did not realize was that she stood to lose nothing. For twenty-six years she had marked time, an uneventful, boring process. Even tending the soldiers had added some color, some shading, however drab, to the pale canvas of her life.

Dr. McFarland’s prognosis had been the stimulus that had caused her to accept the daring and dangerous challenge offered by the lure of the Western wilderness.

At Fort Whipple, in the central Arizona Territory, Catherine stayed only long enough to eat the roasted wild turkey and plum pudding and unashamedly bask in the attention the soldiers showered on the lone white woman. Then, in order to arrive in Tucson by the date agreed upon with Don Francisco, she had to hurriedly board a privately owned stage line—the only stage that still operated in Arizona since the Civil War had forced the abandonment of the Butterfield Overland. With her traveled the windy old surveyor general who was returning to Tucson after a two-year absence in Washington.

Before the driver cracked his whip over the mules. Governor Goodwin charged Ogilvee to care for Catherine. Tugging at his beard, as if afraid of making some inappropriate remark, the governor said, “You know. Miss Howard, if Tucson is—uh, worse than you expected, write us. We’ll somehow arrange for you to return to the States.”

&nbs

p; She reassured the old gentleman she would be all right, but she had her doubts as the coach, creaking on its leather springs, crawled mile after miserable mile across a desert wasteland that seemed to stretch into infinity. How could land and weather change so abruptly, from snow-blanketed pines to heat-shimmering sands? She dotted at the perspiration beading her hairline with her lace-edged handkerchief and readjusted the porkpie hat’s ribbons that were biting into her chin. If hell was hotter than this, she knew she did not want to go there.

For a while she closed lids heavy with the weight of thick lashes to block the sting of the alkaline dust kicked up by the six-mule team. She willed away the tired face of the surveyor general to dwell on the image of the cool green valley of Tucson’s thickly wooded Santa Cruz River. From that point she allowed herself to speculate more fully on the family for whom she would work.

Don Francisco Godwin had explained briefly in his letter that he wished her to tutor his two grandchildren for a one-year tenure and went on to tell her a little about Cristo Rey, perhaps to whet her appetite, for there were no public schools in the territory and private teachers were difficult to obtain. For that one year she would receive a salary triple that of a public-school teacher, a room of her own, and servants to wait on her in that land of perpetual sunshine.

But she drew her own conclusions, both from Don Francisco’s autocratic letter and from the bits of information delivered by Ogilvee. She suspected Don Francisco of being an opportunist; for what kind of man was he to have sought his fortune by marrying a widow who had inherited the most prized land grant in the territory—a Mexican woman of aristocratic birth whose lines traced back to El Cid and Burgos, Spain?

“Dona Dominica Davalos was not a bad-looker either,” Ogilvee added. “And old Don Francisco, Frank he was then, didn’t seem to mind when he married her that she already had a son—Lorenzo. Wild as a March hare. Of course, Don Francisco’s son, Sherrod, was only four or five years older than Lorenzo, who was six or so at the time. So that helped.”

Renegade Man

Renegade Man Sweet Enchantress

Sweet Enchantress Savage Enchantment

Savage Enchantment Mood Indigo

Mood Indigo Indian Affairs (historical romance)

Indian Affairs (historical romance) AT FIRST SIGHT: A Novella

AT FIRST SIGHT: A Novella The Maidenhead

The Maidenhead Dream Time (historical): Book I

Dream Time (historical): Book I Made For Each Other

Made For Each Other GYPSIES, TRAMPS, AND THIEVES

GYPSIES, TRAMPS, AND THIEVES Deep Purple

Deep Purple Tame the Wildest Heart

Tame the Wildest Heart LAVENDER BLUE (historical romance)

LAVENDER BLUE (historical romance)